Canada, a land of legendary logos and loyal shoppers, has seen many homegrown names vanish despite once being household staples. These weren’t small startups or passing fads, they were national icons that shaped everything from weekend snacks to fashion to travel. Their decline tells a story about changing tastes, economic pressures, and the unstoppable rise of globalization. Here are 20 iconic Canadian brands you didn’t know were gone.

Zellers

Once a national retail giant, Zellers was the go-to for affordable everything, from household goods to back-to-school clothes. Known for its red logo and friendly “club” discounts, it had over 300 locations at its peak. However, in the 2010s, it collapsed after Target acquired its leases, hoping to replicate its U.S. success in Canada. When Target itself failed, Zellers’ brief revival attempts in Hudson’s Bay stores couldn’t regain its former charm. Today, only a few pop-up locations exist, more for nostalgia than commerce. For many Canadians, Zellers is still remembered for its cafeteria fries and unbeatable “lowest price” jingle.

Target Canada

Although an American brand, Target’s 2013 entry into Canada was met with overwhelming excitement, only to crash spectacularly within two years. Poor inventory management, higher prices than in the U.S., and empty shelves quickly eroded public goodwill. Canadians expected the trendy, affordable experience they saw across the border but got confusion instead. By 2015, Target Canada shuttered all 133 stores, leaving nearly 17,000 employees jobless. It became one of the fastest and most expensive retail failures in Canadian history. Even today, many shoppers recall the heartbreak of seeing “liquidation sale” signs instead of the stylish aisles they were promised.

Eaton’s

Eaton’s was more than a store; it was an institution. Founded in 1869, it once defined Canadian retail with flagship locations, catalogs, and even its own parade. Generations grew up shopping at Eaton’s for everything from wedding China to Christmas toys. But by the 1990s, competition from discount retailers and a lack of modernization led to its decline. The company filed for bankruptcy in 1999, ending 130 years of history. The Eaton Centre malls in Toronto and Montreal still bear its name, but the empire itself is long gone, a bittersweet reminder of Canada’s once-proud department store culture.

Sears Canada

Sears was the catalog king for decades, especially for rural families who depended on its mail-order convenience. The brand thrived in the 1980s and 1990s, offering affordable appliances, tools, and clothing. But digital disruption and outdated management models caught up with it. By 2017, Sears Canada filed for bankruptcy, closing all stores and cutting thousands of jobs. The loss hit hard in smaller communities where Sears was often a mainstay. Many Canadians still miss its dependable “Kenmore” appliances and the thick Christmas Wish Book that once symbolized the magic of holiday shopping before everything went online.

Future Shop

Tech enthusiasts once treated Future Shop as their playground. Founded in 1982 in Vancouver, it grew into one of the country’s top electronics retailers. When Best Buy entered Canada and later acquired it, the writing was on the wall. In 2015, Best Buy closed all Future Shop locations, converting some into Best Buys. The brand’s disappearance symbolized the loss of a uniquely Canadian take on tech retail. Future Shop’s signature red branding, high-energy ads, and “we’ll beat any price” promise made it iconic in its time. Now, Canadians shop for gadgets without the familiar rush of red signage.

Canadian Airlines

Before Air Canada’s dominance, Canadian Airlines flew the maple leaf proudly across international skies. Formed from a merger in 1987, it served major routes worldwide and was known for its friendly service and safety record. Financial difficulties and rising competition, however, grounded the company by 2001 when Air Canada acquired it. Its blue goose logo and slogan, “A world of difference”, still evoke nostalgia for travelers who remember its distinctly Canadian service culture. For aviation enthusiasts, Canadian Airlines remains a symbol of national pride lost in the turbulence of airline consolidations.

Northern Getaway

If you grew up in the ‘90s, you probably had a Northern Getaway sweater with a moose or polar bear on it. The children’s clothing brand was famous for its cozy designs, bright colors, and Canadiana themes. Sold in malls nationwide, it represented playful, affordable fashion for kids. As international brands like Gap Kids and H&M entered the scene, Northern Getaway couldn’t compete. It quietly disappeared in the 2000s, leaving a generation nostalgic for its fuzzy animal logos. Vintage pieces occasionally surface online, treasured by millennials who grew up wearing its proudly Canadian prints.

BiWay

The discount chain BiWay was a budget shopper’s paradise in the 1980s and 1990s. Known for its “Everything’s $1.00” deals long before Dollarama, it offered basics, school supplies, and quirky finds for low-income families. Despite its popularity, BiWay couldn’t withstand competition from Walmart and Dollarama’s aggressive expansion. By 2001, the last stores closed. Attempts to revive BiWay under “BiWay $10 Store” branding in recent years fizzled. Its fall marked the end of a uniquely Canadian discount culture where you could fill a bag and still have change for coffee.

Sam the Record Man

Music lovers once flocked to Sam the Record Man on Toronto’s Yonge Street, its neon spinning discs glowing like a cultural landmark. The store, founded in 1937, was the heart of Canada’s music retail scene. Whether you wanted rock, jazz, or indie records, Sam’s had it all. But as digital downloads and streaming rose, physical media sales collapsed. The flagship store closed in 2007, and though the sign was preserved, the business never returned. Sam’s decline mirrored the death of the record store era, when browsing aisles and discovering albums was an experience, not just a click.

Beaver Lumber

Before Home Depot and Lowe’s took over, Beaver Lumber was Canada’s go-to for DIY projects and home repairs. Founded in 1906, the chain had over 130 stores nationwide. Its friendly service and community-based approach made it a fixture in small towns. But by the late 1990s, the rise of big-box hardware stores crushed smaller competitors. Home Hardware bought Beaver Lumber in 1999, effectively ending the brand. The loss symbolized a shift from neighborhood hardware stores to impersonal warehouse retailing. Older Canadians still remember Beaver Lumber as a place where you could get both advice and lumber in one trip.

Jacob

Jacob was a mall fashion mainstay for young women seeking stylish yet affordable clothes. Founded in Montreal, the brand gained popularity for its modern workwear and trendy dresses. However, fast fashion retailers like Zara and H&M disrupted the market with cheaper prices and quicker collections. Jacob filed for bankruptcy in 2014, closing all stores. Attempts to relaunch online were short-lived. The brand’s fall showed how even locally beloved labels couldn’t withstand global retail giants. Many shoppers still recall Jacob’s chic window displays and how it once made “business casual” look effortlessly cool.

Canadian Tire Gas+

Canadian Tire’s gas stations were once a familiar stop for road-trippers, offering “Canadian Tire money” rewards and convenient fuel prices. But as the company shifted focus to retail, banking, and loyalty programs, the Gas+ division began to shrink. Many locations were sold to other fuel companies by the late 2010s. While the main brand thrives, the standalone Gas+ name has quietly faded in most regions. For many, the red-and-green signage was part of the quintessential Canadian road trip, now replaced by the generic glow of multinational fuel brands.

Grand & Toy

Office workers once depended on Grand & Toy for everything from pens to printers. Founded in 1882, it dominated Canada’s office supply market for decades. But as online retailers like Amazon rose and remote work reduced traditional office needs, the company struggled to stay relevant. By 2014, Grand & Toy closed its physical stores and moved entirely online, effectively ending its in-store presence. Though technically not gone, the brand’s tangible retail identity vanished. Its closure marked the end of an era when shopping for office supplies meant more than just clicking “add to cart.”

Tip Top Tailors (Original Era)

Though the name still exists, the original Tip Top Tailors empire that once defined Canadian menswear is long gone. Founded in 1909, it was known for custom suits and fine tailoring made domestically. After several ownership changes and foreign acquisitions, production moved overseas, and the brand’s Canadian-made legacy faded. The company that once dressed generations of men for their first jobs and weddings became just another chain in mall corridors. While the logo survives, the spirit of the original Tip Top, proudly made-in-Canada craftsmanship, disappeared with its factories.

Dominion Stores

Dominion was a supermarket legend, known for its “Main Street” feel and focus on fresh produce. Founded in 1919, it became one of the largest grocery chains in Ontario and Newfoundland. But corporate mergers and acquisitions led to its gradual erasure. By the early 2010s, most stores had been rebranded as Metro or Loblaws. The name Dominion faded from storefronts, ending nearly a century of grocery history. Its loss represented the consolidation of Canadian retail into a handful of national giants, efficient, perhaps, but missing the character that made weekly grocery trips feel local.

Consumers Distributing

This hybrid between catalog and retail shopping was revolutionary in the 1970s and 1980s. Customers browsed catalogs, filled out forms, and waited for staff to retrieve products from the back. The model worked until e-commerce made it obsolete. By 1996, Consumers Distributing shut down, unable to compete with real-time inventory systems. Still, many remember the thrill of flipping through its thick seasonal catalogs, circling toys or electronics they wanted for Christmas. It was a pre-Amazon version of wish-list shopping, now remembered fondly as a relic of a slower, simpler retail age.

Beaver Foods (St. Hubert Chicken)

Before rotisserie chicken chains exploded nationwide, Beaver Foods (the parent company of St. Hubert in some regions) provided hearty comfort meals with a distinctly local flavor. While St. Hubert survives in Quebec, its broader national footprint vanished as fast-food giants and delivery apps changed dining habits. Mergers and franchising struggles led to closures outside its home province. The golden-yellow packaging and rich brown gravy once defined family dinners. Though the St. Hubert name endures, Beaver Foods’ national legacy, once a serious rival to Swiss Chalet, faded from dining maps.

Clearnet

Before the Telus takeover, Clearnet was a trailblazer in mobile communication. Its quirky ads featuring animals and the slogan “The future is friendly” set it apart in the 1990s telecom boom. Clearnet was innovative, offering pay-as-you-go plans long before they were standard. When Telus acquired it in 2000 for over $6 billion, the brand disappeared but its DNA lived on, Telus even adopted its slogan and aesthetic. Though short-lived, Clearnet left a big mark on Canada’s mobile industry, proving that creativity and customer-first innovation could thrive before corporate giants consolidated the field.

Kraft Canada (as a standalone brand)

While Kraft products still line shelves, the Canadian arm of Kraft ceased to exist after its 2012 merger with Heinz. The combined company centralized operations in the U.S., effectively dissolving Kraft Canada’s independence. Many Canadians felt the change, as recipes, packaging, and even product lines were altered. Classics like Kraft Dinner and Cheez Whiz remained, but the distinctly Canadian approach to branding, like bilingual packaging and local flavor variations, was lost. The disappearance of Kraft Canada marked a quiet end to domestic influence in one of the country’s most beloved food brands.

Club Monaco (Canadian Ownership)

Launched in Toronto in 1985, Club Monaco revolutionized minimalist fashion before “capsule wardrobes” were trendy. The brand became synonymous with sleek, modern Canadian style. However, in 1999, Ralph Lauren purchased the company, moving its creative direction and headquarters to New York. While stores still exist globally, its identity as a Canadian brand vanished. What was once a proudly homegrown label became just another cog in an American fashion empire. The original Club Monaco represented understated sophistication; today’s version, while stylish, no longer carries that subtle Northern cool that made it iconic.

21 Products Canadians Should Stockpile Before Tariffs Hit

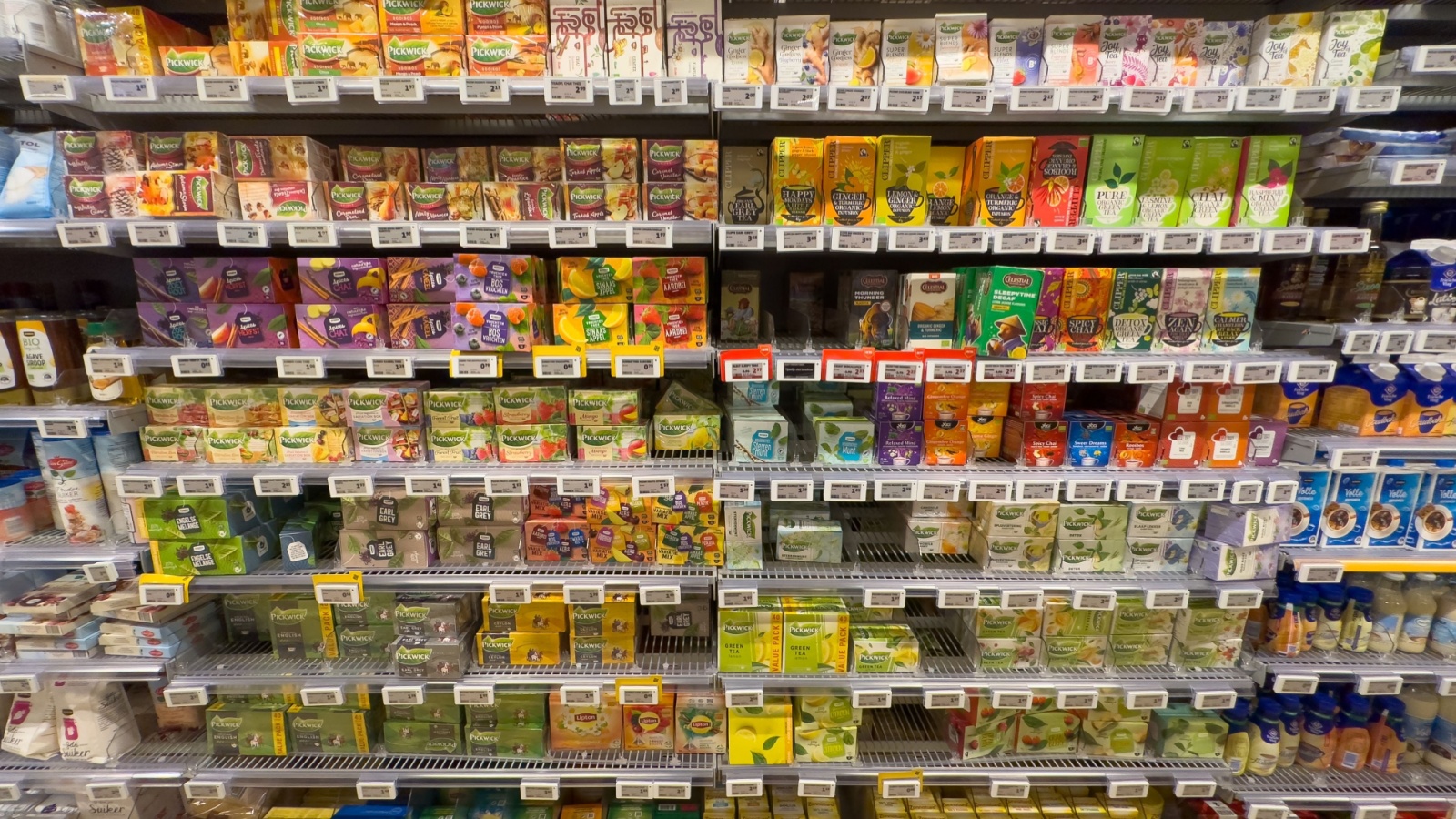

If trade tensions escalate between Canada and the U.S., everyday essentials can suddenly disappear or skyrocket in price. Products like pantry basics and tech must-haves that depend on are deeply tied to cross-border supply chains and are likely to face various kinds of disruptions

21 Products Canadians Should Stockpile Before Tariffs Hit