Canada’s contributions to innovation go well beyond maple syrup. From the labs of universities to rugged northern workshops, Canadian minds have tackled problems that affect daily life globally. Here are 21 Canadian inventors changing the way we live.

Sir Frederick Grant Banting – insulin for diabetes

Sir Frederick Grant Banting helped crack a medical mystery: the hormone insulin, vital for processing blood sugar. He teamed up with Charles Best and James Collip at the University of Toronto in the early 1920s to isolate and purify this hormone. Before that, a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes was essentially a death sentence; afterward, millions worldwide gained hope and treatment. Banting’s work earned him a Nobel Prize in 1923. The ripple effect: Modern endocrinology, diabetic treatment regimes, insulin analogues, this invention opened the door. Without it, daily life, travel, career, and family planning for diabetics would look entirely different.

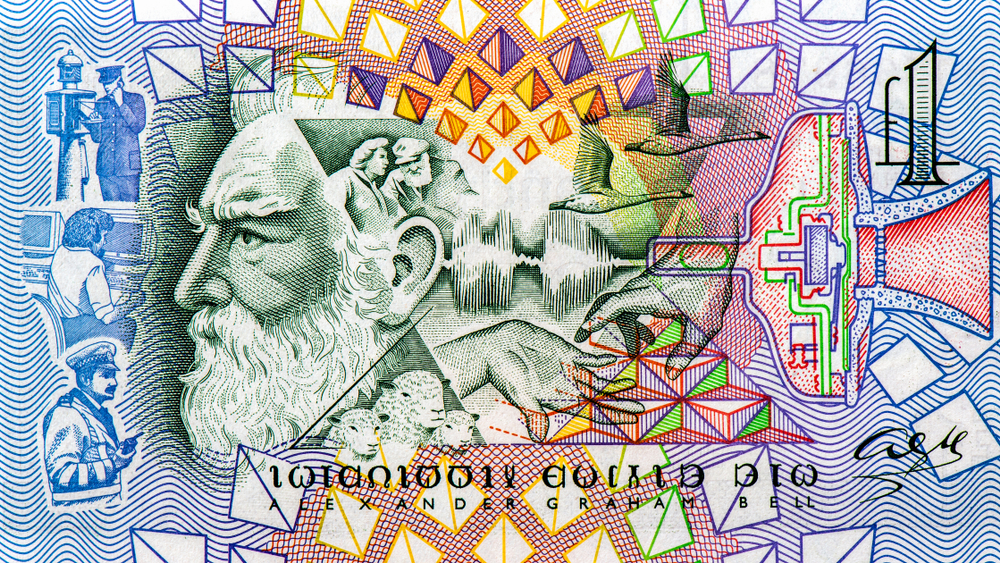

Alexander Graham Bell – telephone

Alexander Graham Bell, though born in Scotland, lived and worked in Canada and invented the telephone while residing in Ontario. That device became the foundation for global voice communication, letting people speak across distances rather than rely on written messages or telegraph wires. The impact spans from business calls to emergency services to personal connections. The telephone transformed how societies function, reshaped cities, commerce, and relationships. Without Bell’s device, our mobile Internet world would have started from a very different place. His invention anchors modern connectivity.

Morse Robb – Robb Wave Electric Organ

Morse Robb is less well-known but significantly influential: He developed the Robb Wave Organ in 1927, a pioneering electronic musical instrument that pre-dated the more widely known Hammond organ. His work applied electronics and acoustics in new ways, demonstrating that machines could replicate and transform musical sound beyond traditional mechanical instruments. That leap paved the way for synthesizers, digital keyboards, and the very fabric of modern electronic music production. Robb’s invention shifted musical possibilities, allowing composers and performers to explore new textures, timbres, and modes of creation.

Joseph-Armand Bombardier – snowmobile

Joseph-Armand Bombardier built a machine for snow and deep-winter mobility: the snowmobile. Growing up in Quebec, he was driven by necessity; his son’s illness during a blizzard underscored the need to reach remote areas. The first commercial “B7” vehicle emerged in the late 1930s. Eventually, the company Ski-Doo became a household name. The invention transformed travel in snowy regions, aided rescue services, supported winter tourism, and opened up access to remote terrain. In places where snow once meant isolation, Bombardier’s machine helped link people, goods, and services.

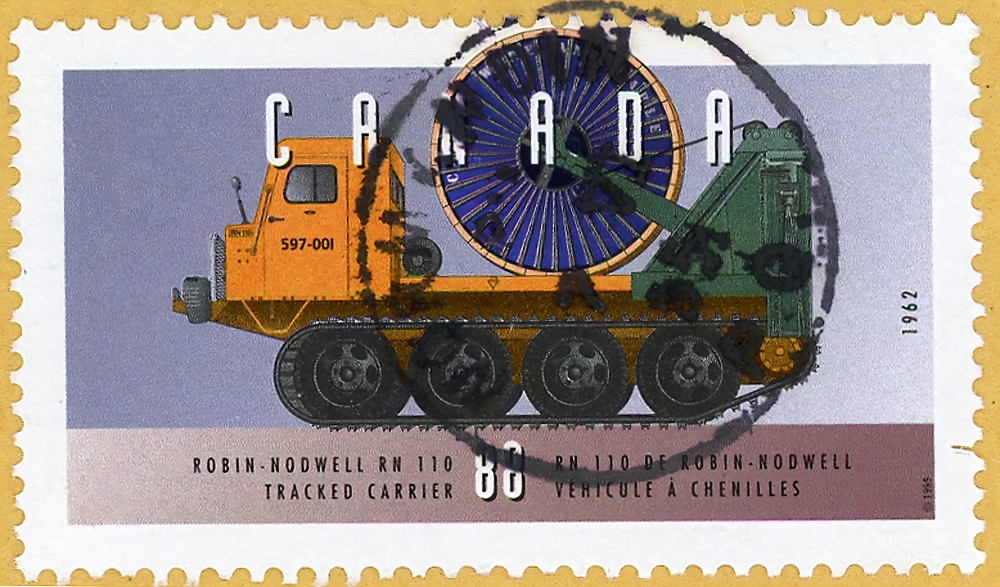

William Bruce Nodwell – track-vehicle for extreme terrain

William Bruce Nodwell designed the Nodwell 110 and other wide-track vehicles capable of traversing muskeg, swamp, snow, and otherwise impassable landscapes. His invention had a huge influence on northern Canada, mineral exploration, and even Antarctic research missions. The ability to move heavy loads across the “impossible” changed industries: oil, logging, exploration, and remote communities. Without such tracked vehicles, northern infrastructure development would have faced greater hurdles. Nodwell’s engineering bridged the terrain-barrier gap and added a flicker of innovation to harsh-climate logistics.

Mike Lazaridis – BlackBerry and mobile communications

Mike Lazaridis co-founded Research In Motion (RIM) and spearheaded the creation of the BlackBerry device, a pioneer of wireless handheld email and smartphone technology. The impact rippled globally: mobile productivity, secure communications, and the shift toward always-connected devices. BlackBerry helped redefine office mobility, business practices, and personal communication. Although later disrupted by competitors, Lazaridis’s invention marked a major turning point in mobile tech, connecting people on the go, changing how we work and play, and proving Canadian tech could lead a global revolution.

Elijah McCoy – automatic lubricating cup (“the real McCoy”)

Elijah McCoy devised an automatic lubricating cup for steam engines and other heavy machinery in 1872. His device allowed machines to keep moving without frequent manual oiling, boosting reliability and efficiency in industrial railways, ships, and factories. The phrase “the real McCoy” is often linked to his invention, meaning the genuine article. McCoy’s contribution matters because the optimization of machine operation is foundational to modern manufacturing, transport, and industrial productivity. Without the lubrication innovation, downtime and maintenance burdens would have been higher.

Nestor Burtnyk – key-frame animation technique

Nestor Burtnyk (with Marcelli Wein) developed the key-frame animation technique at the National Research Council in the 1970s, enabling more efficient and realistic animation in film and computers. The method revolutionized how animated motion is captured, edited, and produced. It shifted the workflow of visual effects, games, and digital media by allowing animators to set primary “key” poses and automate the in-betweening. Without this, digital animation would be far more laborious and slower to evolve. Burtnyk’s technique helped underpin contemporary animation, entertainment, and interactive media.

Thomas Ruttan – air-conditioned railway coach

Thomas Ruttan invented the first air-conditioned train car in 1858, improving passenger comfort on rail systems. In an era when rail travel could be hot, crowded, or cold, his innovation enhanced the travel experience, enabled longer journeys, and improved accessibility. The idea of controlled environmental comfort in transit is now standard worldwide, on buses, trains, and planes. Ruttan’s early invention foreshadowed how transportation would evolve beyond mere motion into comfort, reliability, and user-focused design.

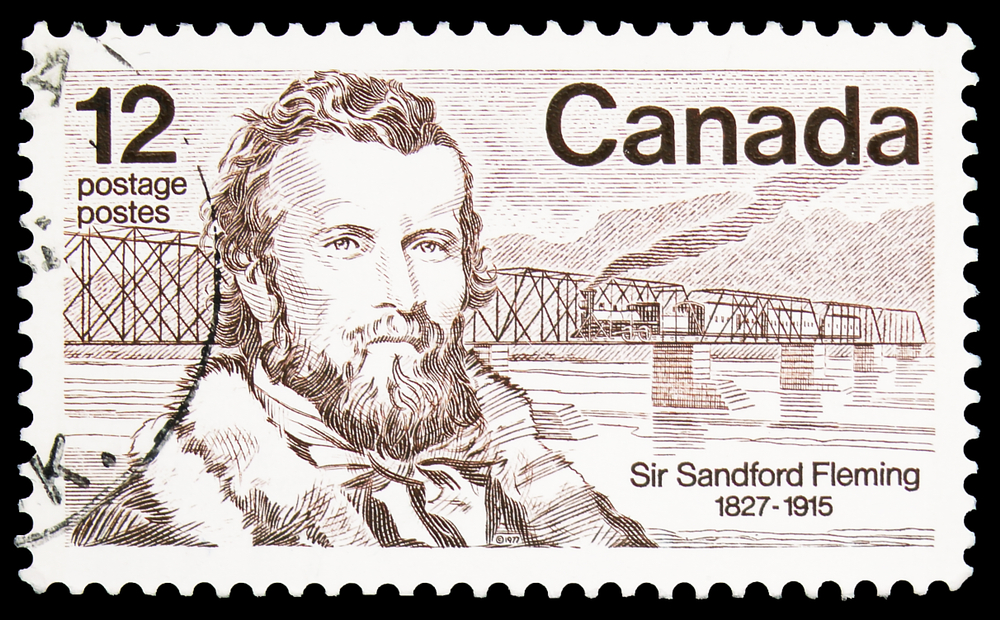

Sandford Fleming – standard time system

Sandford Fleming campaigned for and helped establish the 24-hour clock and worldwide standard time zones in the late 19th century. With growing rail networks and telegraph communication, local times became chaotic. Fleming’s framework clarified scheduling, coordination, and global communication. The standardization of time allowed international transport, finance, and communication systems to scale reliably. Without it, our globalized society would struggle with disparate clocks and unsynchronized systems. Fleming’s contribution underpins modern logistics, global markets, and the digital age.

Peter L. Robertson – Robertson screw and screwdriver

Peter L. Robertson patented the square-socket screw (Robertson screw) in 1908, which improved fastening reliability and ease of use in manufacturing and construction. The design reduced cam-out (screw slipping) and improved worker efficiency, especially in wood construction and automotive assembly. The Robertson system simplified production and maintenance worldwide. It may seem mundane, but manufacturing economies depend on such efficient mechanical standards. Without Robertson’s design, assembly lines and construction might face more errors, slower build times, and higher costs.

Arthur Sicard – snow-blower

Arthur Sicard developed the powered snow-blower around 1927 in Quebec, responding to the challenge of clearing snow from roads. His mechanical innovation allowed towns and cities to maintain mobility during harsh winters, reducing isolation and improving infrastructure resilience. Snow-blowing equipment evolved into standard municipal tools, road-maintenance fleets, and residential devices. Without this invention, severe winter environments would pose greater transportation and safety obstacles in Canada and similarly cold regions around the globe.

Norman Breakey – paint roller

Norman Breakey invented the paint roller in 1940 in Toronto, enabling faster and more uniform painting of walls and ceilings. Before his tool, painting large surfaces was laborious, with brushes dominating. The roller simplified DIY and professional painting alike, reducing time and improving finish. As surfaces became larger (office towers, homes, commercial spaces), his invention scaled the ease of aesthetic renovation and maintenance. Without the paint roller, the cost and effort of painting would remain higher, affecting everything from home improvement to commercial refurbishment.

Louise Poirier – push-up bra (Wonderbra Model 1300)

Louise Poirier designed the Model 1300 push-up bra in 1964, which became widely known under the brand name “Wonderbra.” Her innovation in women’s undergarments significantly changed fashion, body confidence, and garment industry standards. It allowed enhanced bust shaping, creating new aesthetic possibilities and consumer demand. The garment industry evolved through this invention: marketing, branding, mass production, and global fashion trends shifted. Without Poirier’s design, the commercial modern push-up bra category might have looked very different.

Thomas Woodward – improved electric light-bulb patent

Thomas Woodward and Mathew Evans patented an early version of the electric light bulb in 1874 in Toronto, using carbon rods in a nitrogen-filled glass cylinder. While not the final commercial version, the work contributed to electric illumination. Their design preceded some of the mainstream developments and shows Canada’s role in early lighting innovations. Electric lighting transformed nightlife, industry, homes, and urban planning. Without such early work, the march toward widespread electrification and illumination would have progressed differently.

Donald Hings – walkie-talkie

Donald Hings (along with Irving “Al” Gross) invented an early version of the walkie-talkie in 1942 for military use. That portable two-way radio device enabled communications on the move, especially in wartime contexts. Subsequently, the concept filtered into civilian uses: mountain rescue, expedition teams, event coordination, and commercial communication. The ability for mobile instant communication has become essential today (though via smartphones). Without Hings’s portable radio innovation, mobile communication might have developed more slowly or along different lines.

James Gosling – Java programming language

James Gosling developed the Java programming language in 1994 while working at Sun Microsystems, though his Canadian affiliation is noted. Java became one of the most widely used languages, powering mobile apps, enterprise software, embedded systems, and web services. Its “write once, run anywhere” paradigm helped standardize cross-platform development. The impact spans billions of devices worldwide. Without Java, the software world might fragment more severely, and portability would be harder. Gosling’s work influenced software development, almost invisibly but extensively, in everyday devices.

Dianne Croteau – CPR mannequin

Dianne Croteau developed the CPR training mannequin in 1989, allowing realistic practice of cardiopulmonary resuscitation in controlled settings. Her invention improved life-saving training worldwide: medical providers, first-responders, and laypeople now practice on lifelike dummies rather than textbooks. This leads to better preparedness, higher survival rates, and standardized resuscitation protocols. Without such training tools, CPR education would rely more on theory than hands-on experience, likely reducing overall effectiveness in emergencies.

Jean-Jacques Archambault – 735 kV power line technology

Jean-Jacques Archambault contributed to the development of the 735 kV long-distance electricity transmission standard in Quebec in the 1960s, one of the highest-voltage systems of its time. Through this innovation, large-scale power generation and transmission over vast distances became more feasible, reducing losses and enabling remote generation sites to feed cities. Efficient electricity distribution underpins modern economies, digital systems, and urban life. Without advancements like Archambault’s, energy infrastructure would be less robust and higher cost.

Joseph Coyle – egg carton

Joseph Coyle invented the egg carton in 1911 in Smithers, British Columbia, after witnessing conflict between a farmer and a hotelier over broken eggs. His simple packaging innovation reduced breakage, simplified transport, and became standard for millions of eggs worldwide. Packaging may seem mundane, but it affects food distribution, shelf life, logistics, and waste. Without Coyle’s design, the humble egg delivery system and retail distribution might remain less efficient, with higher costs and more waste.

Rachel Brouwer – low-cost water-purification system

Rachel Brouwer developed a low-cost water-purification system while still a high-school student, using ABS pipe, bottles, charcoal, cotton, and a temperature-indicator wax made from soybean to signal safe drinking. Her invention targets water safety in low-resource settings, providing bactericidal purification requiring no fuel. The system has seen pilot use in African countries and illustrates how grassroots invention can address global humanitarian issues. Without innovations like hers, safe drinking water access would remain more limited in vulnerable regions.

21 Products Canadians Should Stockpile Before Tariffs Hit

If trade tensions escalate between Canada and the U.S., everyday essentials can suddenly disappear or skyrocket in price. Products like pantry basics and tech must-haves that depend on are deeply tied to cross-border supply chains and are likely to face various kinds of disruptions

21 Products Canadians Should Stockpile Before Tariffs Hit